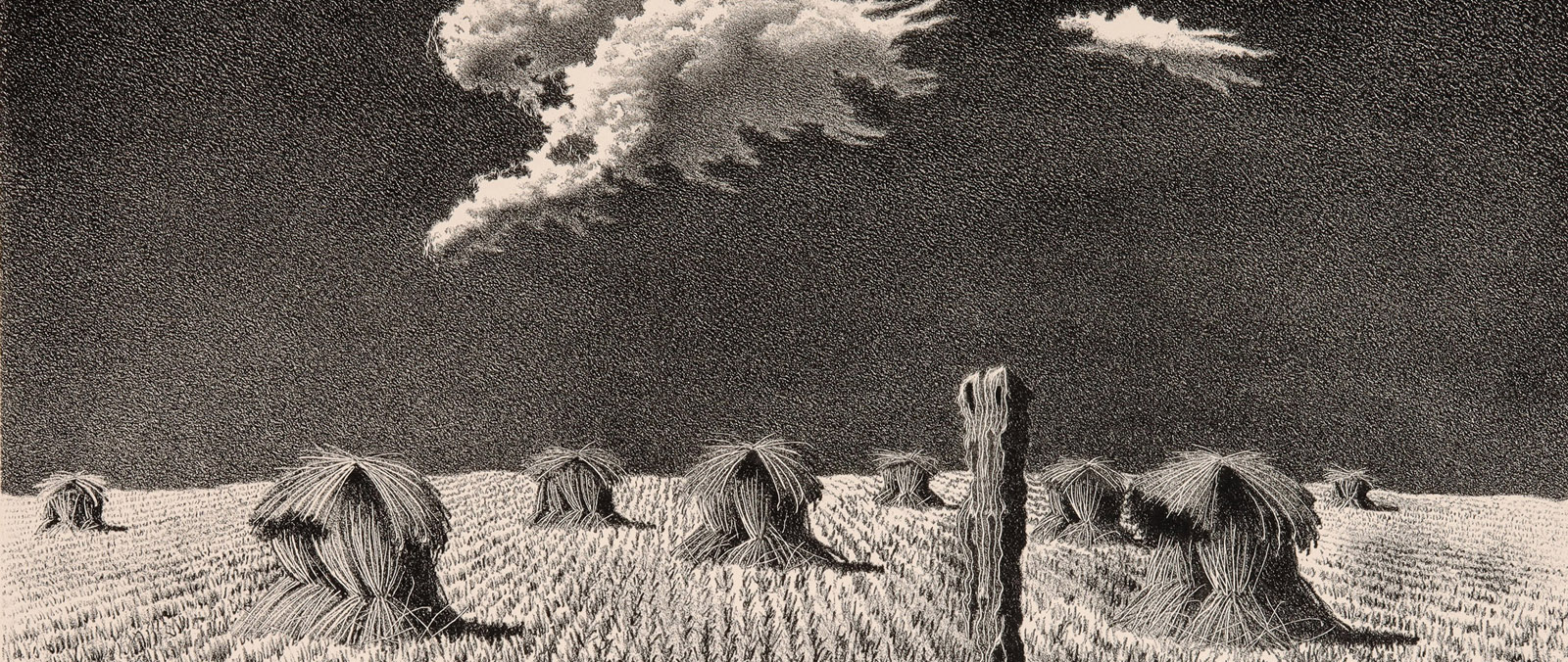

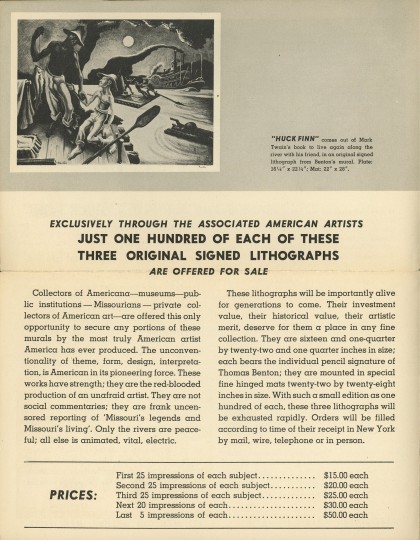

The concept of artists making pencil signed prints based upon their great paintings gained real traction with Whistler in the 1870s. By the mid-1930s, the concept was becoming increasingly popular, and profitable, thanks in large part to an organization known as the Associated American Artists.

Founded in 1934 on the boundless passion of New York art dealer Reeves Lewenthal, the AAA circumvented traditional gallery approaches to obtaining fine art, something Reeves saw as serving only the elites, and instead brought fine prints to the previously passed-over Middle Class. There’s a good chance his idea simultaneously served to boost some artists into that Middle Class, as well. Or at least helped them avoid starvation.

Lewenthal’s goal was to democratize art consumption and art ownership by making art more accessible and more affordable to more Americans. His organization commissioned well-known American artists to create prints, which were then sold at reasonable prices, often for as little as $5 or $10 (still no small sum since that translates to $200 in today’s money). A client of our auctions, now passed, tells of buying Photographing the Bull by T.H. Benton at the UMKC Bookstore in the 1950s for $15. As with this example, the AAA managed to get its artists exposure in less-exclusive settings like department stores and other non-gallery outlets, while advertising its mail-order catalogs in newsprint and on the radio. This brought fine art to a broader range of people while, again, granting artists the opportunity to earn much-needed income through the sale of prints. Without this, a great painting may come to fruition, but once completed, there’s only one – and it may take a long time to sell. Prints of that same composition, while less valuable, offered the artist more opportunity for income. This was particularly valuable during the Great Depression.

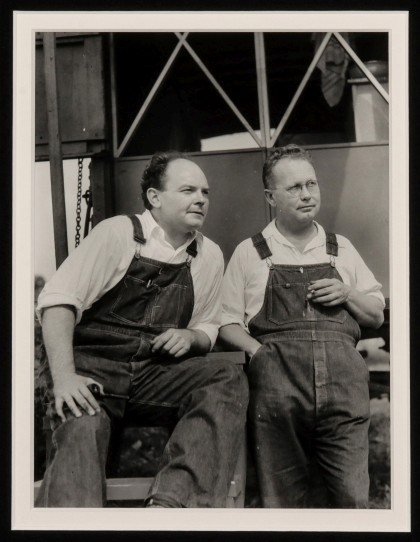

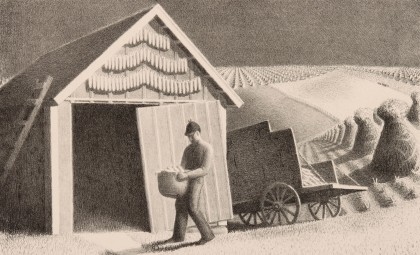

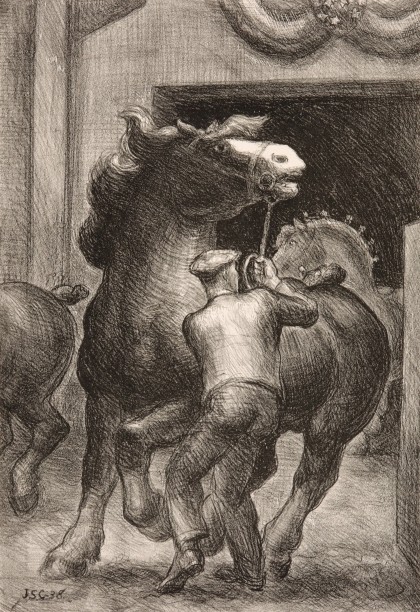

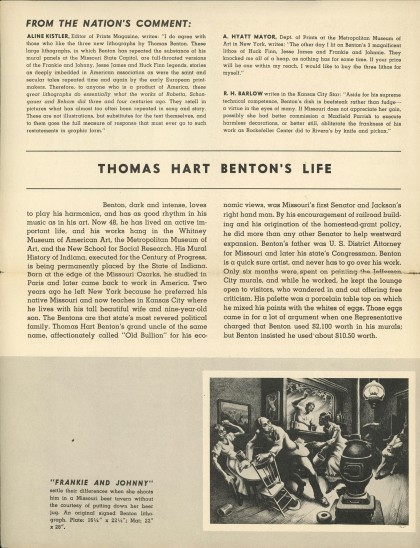

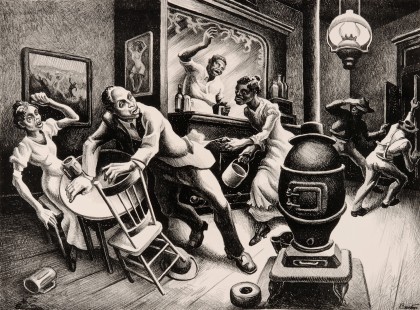

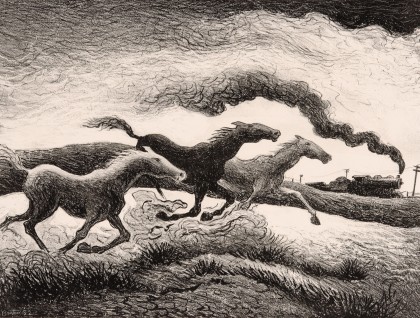

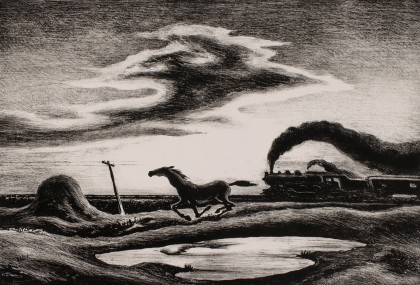

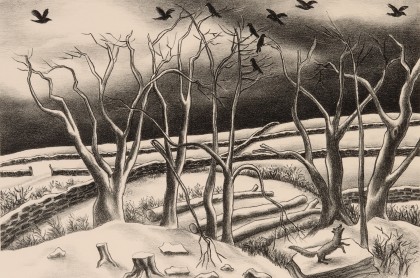

The Regionalist triumvirate of Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton are good examples of Lewenthal’s theories in practice. While they were fortunate to be established and recognized artists when financial crisis struck, it’s doubtful they were immune to the effects of the Great Depression. So, the opportunity to derive a little income from the patronage of the ‘masses’, between commissions and the occasional sale to the ‘classes’, was surely a welcome windfall. They each enjoyed enough success through printmaking, thanks to the Associated American Artists, that it surely helped to pay some bills. The sheer volume of output by Thomas Hart Benton (18 lithographs in the 1930s alone) suggests it must have made a difference financially and possibly as a promotional tool. Benton, and his students, exhibited their original work at the AAA’s galleries in New York more than a few times, as did many others. It’s interesting to note that many examples of prints issued by the Associated American Artists during this period are now held in the collections of major museums.

Grant Wood, who was very devoted to his sister and helped support her during hard times, is a good example of how Lewenthal's brainchild paid dividends. When the AAA commissioned Wood to create a special edition commemorating the organization's fifth anniversary, the artist was able to employ his sister Nan (the model for the farmer's wife in American Gothic) and her husband Ed, paying them per print to hand-color a series of lithographs titled Wild Flowers, Tame Flowers, Fruits and Vegetables. It took three years to complete the series of one thousand prints. The final product was available by mail order at $10 per print in 1939.

Postscript: The model for the farmer in American Gothic was Grant Wood’s dentist, Dr. Byron Henry McKeeby of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.